World Skin, a Photo Safari in the Land of War

Virtual Reality, CAVE, cameras, printer, Internet

World Skin is an interactive artwork presented for the first time at Ars Electronica (Linz, Austria). It won the Golden Nica Award in the Interactive Art category in 1998.

Text by Maurice Benayoun, from the Ars Electronica Catalogue 1998.

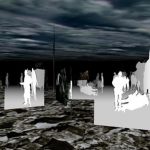

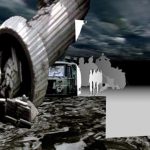

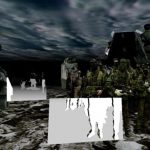

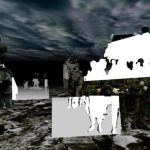

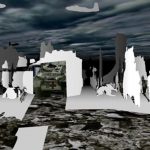

Armed with cameras, we are making our way through three-dimensional space. The landscape before our eyes is scarred by war-demolished buildings, armed men, tanks and artillery, piles of rubble, the wounded and the maimed. This arrangement of photographs and news pictures from different zones and theaters of war depicts a universe filled with mute violence. The audio reproduces the sound of a world in which to breathe is to suffer. Special effects? Hardly. We, the visitors, feel as though our presence could disturb this chaotic equilibrium, but it is precisely our intervention that stirs up the pain. We are taking pictures; and here, photography is a weapon of erasure.

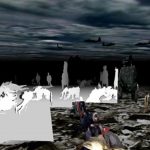

The land of war has no borders. Like so many tourists, we are visiting it with camera in hand. Each of us can take pictures, capture a moment of this world that is wrestling with death. The image thus recorded exists no longer. Each photographed fragment disappears from the screen and is replaced by a black silhouette. With each click of the shutter, a part of the world is extinguished. Each exposure is then printed out. As soon as an image is printed to paper, it is no longer visible on the projection screen. All that remains is its eerie shadow, cast according to the viewer’s perspective and concealing fragments of future photographs. The farther we penetrate into this universe, the more strongly aware we become of its infinite nature. And the chaotic elements renew themselves, so that as soon as we recognize them, they recompose themselves once again in a tragedy without end.

We take pictures. First by our aggression, then feeling the pleasure of sharing, we rip the skin off the body of the world. This skin becomes a trophy, and our fame grows with the disappearance of the world.

Here, being engulfed by war is an immersion in a picture, but it is a theatrical performance as well. In the sequence of events which characterize the story of a single person, war is an exceptional incident which reveals humanity’s deepest abyss. It promotes the process of reification of another human being. Taking pictures expropriates the intimacy of the pain while, at the same time, bearing witness to it.

This has to do with the status of the image in our process of getting a grasp on this world. The rawest and most brutal realities are reduced to an emotional superficiality in our perception. Acquisition, evaluation and understanding of the world constitute a process of capturing it. Capturing means making something one’s own; and once it is in one’s possession, that thing can no longer be taken by another.

In French, “prise de vues.” Shooting, taking. In the case of a material storage medium, “taking” something is the equivalent of taking it with you. Photography captures the light reflected by the world. It constitutes an individual process of capturing and arranging. The image is adapted to the viewfinder.

The picture neutralizes the content. Media bring everything onto one and the same level. Physical memory-paper, for example, is the door that remains open to a certain kind of forgetting. We interpose the lens (“objectif” in french) between ourselves and the world. We protect ourselves from the responsibility of acting. One “takes” the picture, and the world “proffers” itself as a theatrical event. The world and the destruction constitute the preferred stage for this drama-tragedy as a play of nature in action.

The living are the tourists of death. If art is a serious game, then so is war. War is a game in which the body is placed at risk as an incessantly, unremittingly posed question of the reduction of existence to its bare remains.

The printed trace is the counterpart of forgetting. A “good conscience” is a contradiction of a “good memory.” One knows what one has retained, but one does not know what one has stricken from one’s memory.

Here, the viewer/tourist contributes to an amplification of the tragic dimension of the drama. Without him, this world is forsaken, left to its pain. He jostles this pain awake, exposes it. Through the media, war becomes a public stage, in the sense in which a whore might be referred to as a “public woman.” Pain reveals its true identity on this obscene stage, and all are completely devoured. The sight of the wounded calls to mind the image of a human being as a construct which can be dismantled. Material, more or less. The logic of the material holds the upper hand over the logic of the spirit, the endangered connective tissue of the social fabric.

War is a dangerous, interactive community undertaking. Interactive creation plays with this chaos, in which placing the body at stake suggests a relative vulnerability. The world falls victim to the viewer’s glance, and everyone is involved in its disappearance. The collective unveiling becomes a personal pleasure, the object of fetishistic satisfaction. We keep to ourselves what we have seen (or rather, the traces of what we have seen). To possess a printed vestige, to possess the image inherent in this is the paradox of the virtual, which is better suited to the glorification of the ephemeral. The soundtrack is there to enable us to go beyond the play of images and to experience this immersion as real participation in the drama. In sharp contrast to the video games that transform us into passionate warriors, here the audio unmasks the true nature of apparently harmless gestures and seeks to provide not so much a form of comprehension as a form of experience. Some things cannot be shared. Among them are the pain and the image of our remembrance. The worlds to be explored here can bring these things closer to us — but always simply as metaphors, never as a simulacrum.

The apparatus

The immersive room

The projection space can be a single screen or a cubic immersive room whose walls, and floor, are screens. Some immersive rooms use also the roof as a screen. Visitors can shift direction by facing in different directions. Everything happens as in life. In each group of tourists visiting World Skin, the driver can individually decide about the internal navigation. Collective decisions can also be taken according to group consensus. According to the immersive room size, an expandable number of spectators can participate. Through the open wall of the CAVE, the audience can witness, although not interactively. The visitors and the audience can use shutter glasses in order to get a stereo view. This is the best way to avoid the painted-wall effect.

The navigation :

Only the driver using a “wand” can decide about the group trip. In this way, he has the role of a “bus driver”. Everyone can ask about the path alterations.

The photographers

The particiapants are active. They have to decide about the group’s movements. Otherwise they cannot take pictures of what they are seeing. Several cameras hanging from the ceiling allow them to take photos. Instead of opening its shutter to capture the image, the camera sends coordinates to the computer at the time of release. The corresponding framing is rerendered in higher definition.

The taken shots

With the camera, the visitor can frame the virtual show at leisure. He chooses angles, frames and release time. Each camera is equipped with magnetic tracker which allows transmission of its exact position in space and its orientation according to 3 axis. Thus, the machine can compute the corresponding frame, in relation to the scene and time of the shot.

The World Skin

For each shot, the corresponding surface (divided into silhouette fragments) is removed from the virtual databases. It looks like a white projection made the set pixels disappear, covered by the camera field. The white fragments constitute a rectangle (the frame), only from the exact point of view of the shot. In other words, the perspective takes over again and we can discover the white surface fragments vanishing into the set depth.

The photography

After the session, the visitor exits the CAVE and finds a printer and a screen presenting the website, where the last shots are sent in real time. He can leave the place with a printed copy of the shots.

The machinery

This installation requires a system able to manage a big number of textures. The original version runs on SGI Onyx. The PC version adapted by Ars Electronica Future Lab runs on Linux PCs. The photographic system requires 1 to 5 real photo cameras (a compact, economical type, but sturdy), modified at the release level and 2 to 6 magnetic or infrared trackers. This computer will be connected to an ordinary color printer.

World Skin exhibitions list

- Ars Electronica Festival, curated by Gerfried Stocker, Linz, Austria, 1997

- Prix Ars Electronica, Golden Nica award, Linz 1998

- Siggraph Art Gallery, Touchware exhibition, curator Joan Truckenbrod, Orlando, USA, 1998

- Imagina, Monte Carlo, Monaco, 1998

- KTH, Stockholm, Sweden, 1998

- Biennale do Mercosul, World Skin Web site, curator Diana Rodriguez, Brazil, November – December 1999

- VR Center Nord, “World@rt”, curated by Lars Qvortrup, Aalborg, Denmark, 2000.

- Chapelle de l’Ecole Nationale Supérieure des Beaux Arts, Beyond the Screen exhibition, ISEA2000, Paris, 2000

- Multimedia Theater, International Cave Festival Art of Immersion, World Skin, Bonn, Germany, June, 2002

- Museum of the Moving Image Museum, New York, 2004

- Eyebeam, Digital Avant-Garde exhibition, Curated By Benjamin Weill, New York, 2004

- FACT, Liverpool, Sk-interface exhibition, curated by Jens Hauser, 2008

- Nemo Festival, La Bellevilloise, curated by Gilles Alvarez, Paris, 2008

- Casino, Sk-interface exhibition, curated by Jens Hauser, Luxembourg, 2009

- Game Play exhibition, Itau Cultural, Sao Paulo, curated by Brasil, 2009

- V2 Institute of the Unstable Media, Tools for propaganda exhibition, Rotterdam, Nederland, 2010

- FIAC, Show Off, Espace Cardin, curated by Dominique Moulon, Paris, 2013 (World Skin Shots)

Credits

Creation: Maurice Benayoun

Music : Jean-Baptiste Barrière

Software : (SGI, Z.A) Patrick Bouchaud, Kimi Bishop, David Nahon

Ars Electronica engineering: (AE FuturreLab team) Eric Berger, Gilbert Netzer

Graphic support: Raphaël Melki

Production: Ars Electronica FutureLab, Z.A Production,

Support: Silicon Graphics Europe