Art Impact, Collective Retinal Memory

VR, Internet, Interactive Art, interactive Music

Conception: Maurice Benayoun

Music: Jean-Baptiste Barrière

First exhibition Centre Pompidou, Paris, 2000

Curator: Daniel Soutif,

Agent: Cyrille Putman

Other venues:

- Kiasma Museum of Art, Helsinky, Finland, June, August, 2001 (curator: Perttu Rastas)

- Stenersen Museum, Ultima Contemporary Music Festival, Oslo, Norway, Oct. 2001

- MIX01, Aarhus, Denmark, 2001

- GlazArt, Instant Video, Nov. 2001

- Abbaye de Maubuisson, QIO, Dec. 2002

Art Impact, collective memory as far as the eye can reach

From the article for the magazine Ecart # 2

The installation Art Impact, Collective Retinal Memory was presented at the Pompidou Centre in Paris from 20 June to 4 July 2000. Since the opening day, a work bearing the same name has been available to visitors on the Internet. The fact that the same work is presented in two modes is problematic with regard to the reception and presentation of the Internet work within a physical exhibition space.

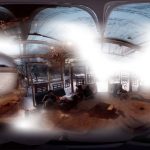

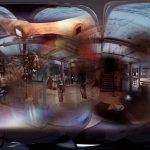

Art Impact, Collective Retinal Memory includes several parallel subject matters. The exposition La Beauté en Avignon (‘Beauty in Avignon’) constitutes the work’s material. The public online or in the Pompidou Centre can actually see some of the venues of the exposition in the form of spherical panoramas. On the Internet, a window opens on top of the spherical photo, and the visitor can look around the place with a feeling of being surrounded by the expository space. The same elements are also present in the exhibition where the visitor can explore the same photographs by using virtual binoculars. Or rather “virtual exploration binoculars”, since it is a physical object that lets us explore the representation by following our movements as they change the viewpoint. There would be nothing very new here if a second photo were not included. On the Internet, the two windows are placed on top of each other. In the exhibition, the first image ? or rather series of images of Avignon ? is visible only with the binoculars, whereas the second one is projected onto a screen 3 m x 12 m. The second image constitutes what I call the ”retinal memory”. This image is also a spherical view, and can be explored similarly to the exposition panoramas. Unlike the Avignon images, this image is composed in real time from the track of multiple looks exploring other images (the different viewpoints of the exposition La Beauté). On the Internet, and on the screen of the Pompidou Centre, everybody can discover the track of other people’s looks, each new track integrating different people’s fragments of interest into a new space, which, in fact, is a space of memory. It is no longer a physical place, diligently interpreted by a necessarily reducive image, but a symbolic assembly of the memory of looks, as if the visitors on the Internet and in the exposition shared a common retina with a revealing rémanance.

The route of the look on the explored world’s surface is not the only track that the visitor leaves behind. In every place there is a soundscape created by Jean-Baptiste Barrière, who starts from recordings made on the spot, attempting to represent the space and the moment by combining the image and sounds captured. The spatial sounds in the Pompidou Centre exhibition follow the topology of the image, mixing the listening track the way the image mixes the track of looks.

The weight of a look in an anthropocentric space

On the Internet, the memory has to be refreshed in order to view your own visual route in the collective retina. In the exhibition, the new state of the retina is updated every second. The binoculars’ field of view is orientated according to the polar co-ordinates, and shows a view seen from the corresponding polar co-ordinates in the Avignon exposition. Changing place during the exploration while maintaining orientation means replacing certain fragments of memory. Fixing on a detail adds more opacity and, therefore, also presence. Zooming in on an object means changing its relative dimension on the retina. The architecture of the memory defines itself progressively as a unified, changing space where the perspective bends according to the spectator’s interest. The space is unified, as it constructs a world around a theoretical spectator, now the sum of visitors. A window of the Popes’ palace touching the exterior of the old tramway repair facility, the vault of the Saint-Charles chapel as the sky. If the result is something more than a patchwork of dispersed places, it is because it is balanced by the look, which gives each integrated fragment an importance in proportion to its potential for retinal attraction. The most impressive elements of each venue are kept, as far as the photographic reduction is concerned. Consisting of a total panorama (360º in both directions), the retina is visible only partially in the exhibition window. To visualise the impact zones, the look of the visitor with the binoculars emphasises the zone under observation. The retinal sphere is, therefore, attracted towards the centre of the image, establishing a gravitational system based on focalisation.

The composition of the resulting image takes place on several levels. The composition depends on the orientation of the explored places (North, South, East, West), it obeys the movements of the viewer, who continuously reproduces the representation, and it has an existence outside the frames, temporarily just off image.

Interface and the movement of the look

User interface as a contact surface between the visitor and the image enables a bi-directional dialogue. It makes the discovery of the masked parts of the image possible while tracing the journey of the look. However difficult it is to follow the look wandering on the surface of an image, it is easy to deduce its focalisation points by following how the image slides on the Internet or how the binoculars move in the expository space. This piece of information becomes the basis of the image composition.

Traceability and the retinal attraction

People can be traced on the Internet. Consequently, nobody is safe from other people’s looks, which is here the determining element in the construction of the meaning. In Avignon, the works and venues are the object of physical exploration. Visitors to the exposition are able to choose their points of view and fully experience the space as a kinaesthetic object; on the Internet, the image offers us only a possibility of a retinal perception of the object. The fact that the intensity of the look is taken into account in order to establish a hierarchy in the composition of the observed elements reduces the perception of art to a visual evaluation of its representation.

La Beauté and after

The Avignon exposition is naturally the determining theme in this project. According to the exposition manager Jean de Loisy, the exposition offers parallel discourses that juxtapose artistic creation and fragments of nature selected by humans on the basis of their aesthetic properties. Art Impact adds to these places and objects other places in Avignon which attract attention for reasons completely other than aesthetic: excavations of fossil worms, a supermarket, slaughterhouses. Tracks in the contact surface human/nature reveal processes connected to survival functions, and the image of these places attracts the public’s retinas just as well as the exposition selection does. It is a permanent battle that takes place in the realms of curiosity, showing the balance of intentions, forms and actions in the memory of looks. Beyond the retina, the memory’s image, in constant mutation, gives meaning to the fight, and rejects all final statements.

Constructing the memory space

Art Impact functions as a representation of the memory by constructing a unique and merging space. The retinal memory in itself is an expository space, which partially bases its choices, continuously available for exploration, on the spectators’ intentions. It also shows the track of these intentions, as if the visitors, in their retinal choices, marked the image with their desires. A virtual space cannot be merely a nonmaterial world. As an information space, it has to construct its own texture, and take into account the new spatio-temporal distribution, which modifies the relations of place and body, memory and time, individual and group. This results in human relocalisation in the peripheral centre of information, where its flow and transitoriness is uncontrollable.

Maurice Benayoun 2000